Listen to this post:

“When did you feel the AGI?”

This is a question that has been floating around AI circles for a while, and it’s a hard one to answer for two reasons. First, what is AGI, and second, “feel” is a bit like obscenity: as Supreme Court Justice Potter Stewart famously said in Jacobellis v. Ohio, “I know it when I see it.”

I gave my definition of AGI in AI’s Uneven Arrival:

What o3 and inference-time scaling point to is something different: AI’s that can actually be given tasks and trusted to complete them. This, by extension, looks a lot more like an independent worker than an assistant — ammunition, rather than a rifle sight. That may seem an odd analogy, but it comes from a talk Keith Rabois gave at Stanford…My definition of AGI is that it can be ammunition, i.e. it can be given a task and trusted to complete it at a good-enough rate (my definition of Artificial Super Intelligence (ASI) is the ability to come up with the tasks in the first place).

The “feel” part of that question is a more recent discovery: DeepResearch from OpenAI feels like AGI; I just got a new employee for the shockingly low price of $200/month.

Deep Research Bullets

OpenAI announced Deep Research in a February 2 blog post:

Today we’re launching deep research in ChatGPT, a new agentic capability that conducts multi-step research on the internet for complex tasks. It accomplishes in tens of minutes what would take a human many hours.

Deep research is OpenAI’s next agent that can do work for you independently — you give it a prompt, and ChatGPT will find, analyze, and synthesize hundreds of online sources to create a comprehensive report at the level of a research analyst. Powered by a version of the upcoming OpenAI o3 model that’s optimized for web browsing and data analysis, it leverages reasoning to search, interpret, and analyze massive amounts of text, images, and PDFs on the internet, pivoting as needed in reaction to information it encounters.

The ability to synthesize knowledge is a prerequisite for creating new knowledge. For this reason, deep research marks a significant step toward our broader goal of developing AGI, which we have long envisioned as capable of producing novel scientific research.

It’s honestly hard to keep track of OpenAI’s AGI definitions these days — CEO Sam Altman, just yesterday, defined it as “a system that can tackle increasingly complex problems, at human level, in many fields” — but in my rather more modest definition Deep Research sits right in the middle of that excerpt: it synthesizes research in an economically valuable way, but doesn’t create new knowledge.

I already published two examples of Deep Research in last Tuesday’s Stratechery Update. While I suggest reading the whole thing, to summarize:

-

First, I published my (brief) review of Apples recent earnings, including three observations:

- It was notable that Apple earned record revenue even though iPhone sales were down year-over-year, in the latest datapoint about the company’s transformation into a Services juggernaut.

- China sales were down again, but this wasn’t a new trend: it actually goes back nearly a decade, but you can only see that if you realize how the Huawei chip ban gave Apple a temporary boost in the country.

- While Apple executives claimed that Apple Intelligence drove iPhone sales, there really wasn’t any evidence in the geographic sales numbers supporting that assertion.

-

Second, I published a Deep Research report using a generic prompt:

I am Ben Thompson, the author of Stratechery. This is important information because I want you to understand my previous analysis of Apple, and the voice in which I write on Stratechery. I want a research report about Apple's latest earnings in the style and voice of Stratechery that is in line with my previous analysis. -

Third, I published a Deep Research report using a prompt that incorporated my takeaways from the earnings:

I am Ben Thompson, the author of Stratechery. This is important information because I want you to understand my previous analysis of Apple, and the voice in which I write on Stratechery. I want a research report about Apple's latest earnings for fiscal year 2025 q1 (calendar year 2024 q4). There are a couple of angles I am particularly interested in:- First, there is the overall trend of services revenue carrying the companies earnings. How has that trend continued, what does it mean for margins, etc.- Second, I am interested in the China angle. My theory is that Apple's recent decline in China is not new, but is actually part of a longer trend going back nearly a decade. I believe that trend was arrested by the chip ban on Huawei, but that that was only a temporary bump in terms of a long-term decline. In addition, I would like to marry this to deeper analysis of the Chinese phone market, the distinction between first tier cities and the rest of China, and what that says about Apple's prospects in the country.- Third, what takeaways are there about Apple's AI prospects? The company claims that Apple Intelligence is helping sales in markets where it has launched, but isn't this a function of not being available in China?Please deliver this report in a format and style that is suitable for Stratechery.

You can read the Update for the output, but this was my evaluation:

The first answer was decent given the paucity of instruction; it’s really more of a summary than anything, but there are a few insightful points. The second answer was considerably more impressive. This question relied much more heavily on my previous posts, and weaved points I’ve made in the past into the answer. I don’t, to be honest, think I learned anything new, but I think that anyone encountering this topic for the first time would have. Or, to put it another way, were I looking for a research assistant, I would consider hiring whoever wrote the second answer.

In other words, Deep Research isn’t a rifle barrel, but for this question at least, it was a pretty decent piece of ammunition.

DeepResearch Examples

Still, that ammunition wasn’t that valuable to me; I read the transcript of Apple’s earnings call before my 8am Dithering recording and came up with my three points immediately; that’s the luxury of having thought about and covered Apple for going on twelve years. And, as I noted above, the entire reason that the second Deep Research report was interesting was because I came up with the ideas and Deep Research substantiated them; the substantiation, however, wasn’t nearly to the standard (in my very biased subjective opinion!) of a Stratechery Update.

I found a much more beneficial use case the next day. Before I conduct a Stratechery Interview I do several hours of research on the person I am interviewing, their professional background, the company they work for, etc.; in this case I was talking to Bill McDermott, the Chairman and CEO of ServiceNow, a company I am somewhat familiar with but not intimately so. So, I asked Deep Research for help:

I am going to conduct an interview with Bill McDermott, the CEO of ServiceNow, and I need to do research about both McDermott and ServiceNow to prepare my questions.

First, I want to know more about McDermott and his background. Ideally there are some good profiles of him I can read. I know he used to work at SAP and I would like to know what is relevant about his experience there. Also, how and why did he take the ServiceNow job?

Then, what is the background of ServiceNow? How did it get started? What was its initial product-market fit, and how has it expanded over time? What kind of companies use ServiceNow?

What is the ServiceNow business model? What is its go-to-market strategy?

McDermott wants to talk about ServiceNow's opportunities in AI. What are those opportunities, and how are they meaningfully unique, or different from simple automation?

What do users think of ServiceNow? Is it very ugly and hard to use? Why is it very sticky? What attracts companies to it?

What competitors does ServiceNow have? Can it be a platform for other companies? Or is there an opportunity to disrupt ServiceNow?

What other questions do you have that would be useful for me to ask?

You can use previous Stratechery Interviews as a resource to understand the kinds of questions I typically ask.

I found the results eminently useful, although the questions were pretty mid; I did spend some time doing some additional reading of things like earnings reports before conducting the Interview with my own questions. In short, it saved me a fair bit of time and gave me a place to start from, and that alone more than paid for my monthly subscription.

Another compelling example came in researching a friend’s complicated medical issue; I’m not going to share my prompt and results for obvious reasons. What I will note is that this friend has been struggling with this issue for over a year, and has seen multiple doctors and tried several different remedies. Deep Research identified a possible issue in ten minutes that my friend has only just learned about from a specialist last week; while it is still to be determined if this is the answer he is looking for, it is notable that Deep Research may have accomplished in ten minutes what has taken my friend many hours over many months with many medical professionals.

It is the final example, however, that is the most interesting, precisely because it is the question on which Deep Research most egregiously failed. I generated a report about another friend’s industry, asking for the major players, supply chain analysis, customer segments, etc. It was by far my most comprehensive and detailed prompt. And, sure enough, Deep Research came back with a fully fleshed out report answering all of my questions.

It was also completely wrong, but in a really surprising way. The best way to characterize the issue is to go back to that famous Donald Rumsfeld quote:

There are known knowns; there are things we know we know. We also know there are known unknowns; that is to say we know there are some things we do not know. But there are also unknown unknowns — the ones we don’t know we don’t know.

The issue with the report I generated — and once again, I’m not going to share the results, but this time for reasons that are non-obvious — is that it completely missed a major entity in the industry in question. This particular entity is not a well-known brand, but is a major player in the supply chain. It is a significant enough entity that any report about the industry that did not include them is, if you want to be generous, incomplete.

It is, in fact, the fourth categorization that Rumsfeld didn’t mention: “the unknown known.” Anyone who read the report that Deep Research generated would be given the illusion of knowledge, but would not know what they think they know.

Knowledge Value

One of the most painful lessons of the Internet was the realization by publishers that news was worthless. I’m not speaking about societal value, but rather economic value: something everyone knows is both important and also non-monetizable, which is to say that the act of publishing is economically destructive. I wrote in Publishers and the Pursuit of the Past:

Too many newspaper advocates utterly and completely fail to understand this; the truth is that newspapers made money in the past not by providing societal value, but by having quasi-monopolistic control of print advertising in their geographic area; the societal value was a bonus. Thus, when Chavern complains that “today’s internet distribution systems distort the flow of economic value derived from good reporting”, he is in fact conflating societal value with economic value; the latter does not exist and has never existed.

This failure to understand the past leads to a misdiagnosis of the present: Google and Facebook are not profitable because they took newspapers’ reporting, they are profitable because they took their advertising. Moreover, the utility of both platforms is so great that even if all newspaper content were magically removed — which has been tried in Europe — the only thing that would change is that said newspapers would lose even more revenue as they lost traffic.

This is why this solution is so misplaced: newspapers no longer have a monopoly on advertising, can never compete with the Internet when it comes to bundling content, and news remains both valuable to society and, for the same reasons, worthless economically (reaching lots of people is inversely correlated to extracting value, and facts — both real and fake ones — spread for free).

It is maybe a bit extreme to say has always been such; in truth it is very hard to draw direct lines from the analog era, defined as it was by friction and scarcity, to the Internet era’s transparency and abundance. It may have technically been the case that those of us old enough to remember newsstands bought the morning paper because a local light manufacturing company owned printing presses, delivery trucks, and an advertising sales team, but we too believed we simply wanted to know what was happening. Now we get that need fulfilled for free, and probably by social media (for better or worse); I sometimes wish I knew less!

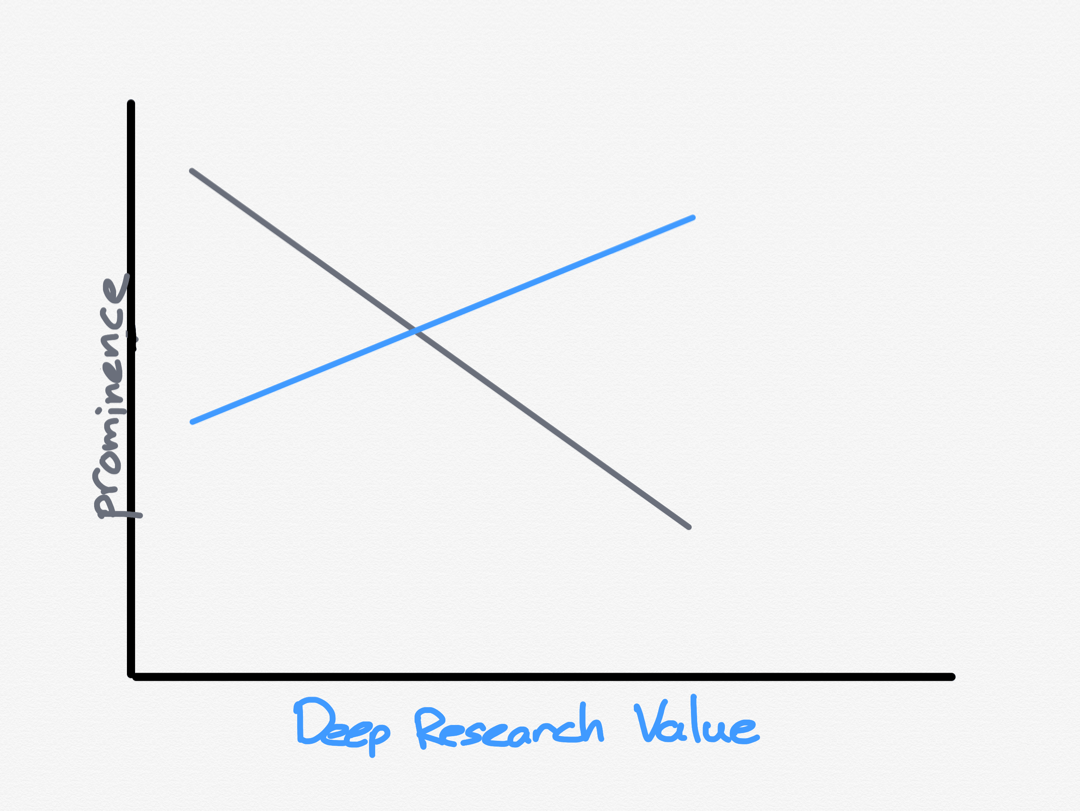

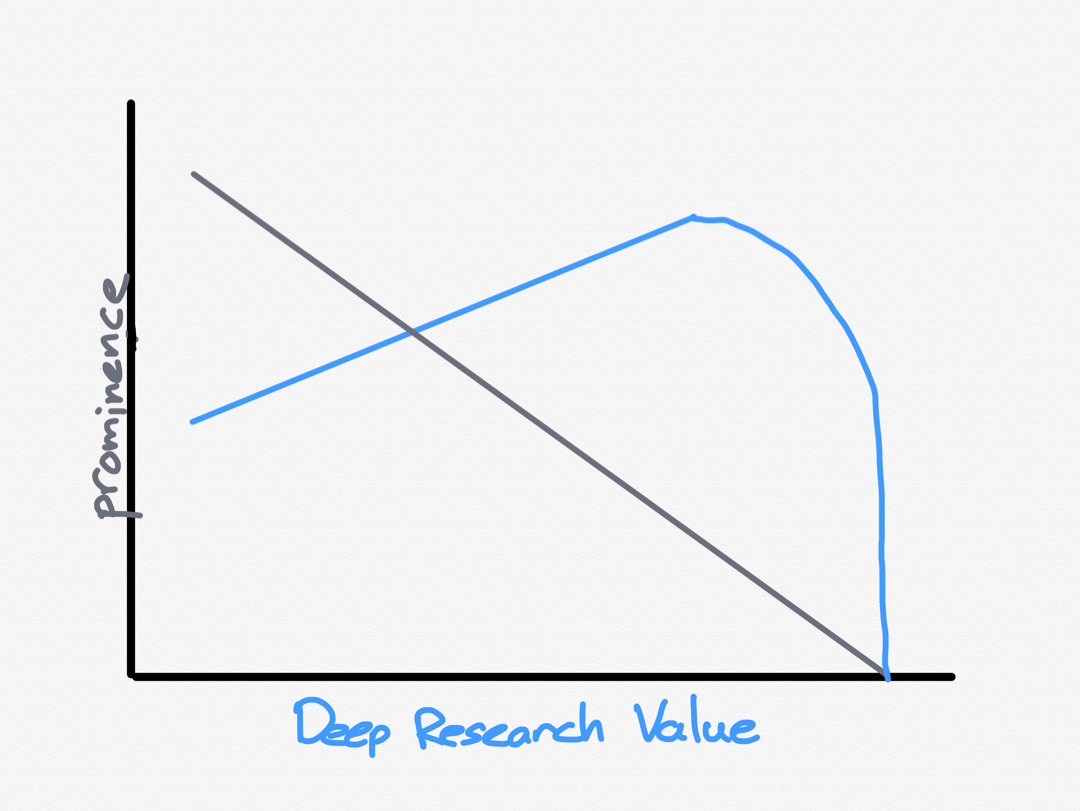

Still, what Deep Research reveals is how much more could be known. I read a lot of things on the Internet, but it’s not as if I will ever come close to reading everything. Moreover, as the amount of slop increases — whether human or AI generated — the difficulty in finding the right stuff to read is only increasing. This is also one problem with Deep Research that is worth pointing out: the worst results are often, paradoxically, for the most popular topics, precisely because those are the topics that are the most likely to be contaminated by slop. The more precise and obscure the topic, the more likely it is that Deep Research will have to find papers and articles that actually cover the topic well:

This graph, however, is only half complete, as the example of my friend’s industry shows:

There is a good chance that Deep Research, particularly as it evolves, will become the most effective search engine there has ever been; it will find whatever information there is to find about a particular topic and present it in a relevant way. It is the death, in other words, of security through obscurity. Previously we shifted from a world where you had to pay for the news to the news being fed to you; now we will shift from a world where you had to spend hours researching a topic to having a topic reported to you on command.

Unless, of course, the information that matters is not on the Internet. This is why I am not sharing the Deep Research report that provoked this insight: I happen to know some things about the industry in question — which is not related to tech, to be clear — because I have a friend who works in it, and it is suddenly clear to me how much future economic value is wrapped up in information not being public. In this case the entity in question is privately held, so there aren’t stock market filings, public reports, barely even a webpage! And so AI is blind.

There is another example, this time in tech, of just how valuable secrecy can be. Amazon launched S3, the first primitive offered by AWS, in 2006, followed by EC2 later that year, and soon transformed startups and venture capital. What wasn’t clear was to what extent AWS was transforming Amazon; the company slowly transitioned Amazon.com to AWS, and that was reason enough to list AWS’s financials under Amazon.com until 2012, and then under “Other” — along with things like credit card and (then small amounts of) advertising revenue — after that.

The grand revelation would come in 2015, when Amazon announced in January that it would break AWS out into a separate division for reporting purposes. From a Reuters report at the time:

After years of giving investors the cold shoulder, Amazon.com Inc is starting to warm up to Wall Street. The No. 1 U.S. online retailer was unusually forthcoming during its fourth-quarter earnings call on Thursday, saying it will break out results this year, for the first time, for its fast-growing cloud computing unit, Amazon Web Services

The additional information shared during Amazon’s fourth-quarter results as well as its emphasis on becoming more efficient signaled a new willingness by Amazon executives to listen to investors as well. “This quarter, Amazon flexed its muscles and said this is what we can do when we focus on profits,” said Rob Plaza, senior equity analyst for Key Private Bank. “If they could deliver that upper teens, low 20s revenue growth and be able to deliver profits on top of that, the stock is going to respond.” The change is unlikely to be dramatic. When asked whether this quarter marked a permanent shift in Amazon’s relationship with Wall Street, Plaza laughed: “I wouldn’t be chasing the stock here based on that.”

Still, the shift is a good sign for investors, who have been clamoring for Amazon to disclose more about its fastest-growing and likely most profitable division that some analysts say accounts for 4 percent of total sales.

In fact, AWS accounted for nearly 7 percent of total sales, and it was dramatically more profitable than anyone expected. The revelation caused such a massive uptick in the stock price that I called it The AWS IPO:

One of the technology industry’s biggest and most important IPOs occurred late last month, with a valuation of $25.6 billion dollars. That’s more than Google, which IPO’d at a valuation of $24.6 billion, and certainly a lot more than Amazon, which finished its first day on the public markets with a valuation of $438 million. Don’t feel too bad for the latter, though: the “IPO” I’m talking about was Amazon Web Services, and it just so happens to still be owned by the same e-commerce company that went public nearly 20 years ago.

I’m obviously being facetious; there was no actual IPO for AWS, just an additional line item on Amazon’s financial reports finally breaking out the cloud computing service Amazon pioneered nine years ago. That line item, though, was almost certainly the primary factor in driving an overnight increase in Amazon’s market capitalization from $182 billion on April 23 to $207 billion on April 24. It’s not only that AWS is a strong offering in a growing market with impressive economics, it also may, in the end, be the key to realizing the potential of Amazon.com itself.

That $25.6 billion increase in market cap, however, came with its own costs: both Microsoft and Google doubled down on their own cloud businesses in response, and while AWS is still the market leader, it faces stiff competition. That’s a win for consumers and customers, but also a reminder that known unknowns have a value all their own.

Surfacing Data

I wouldn’t go so far as to say that Amazon was wrong to disclose AWS’s financials. In fact, SEC rules would have required as much once AWS revenue became 10% of the company’s overall business (today it is 15%, which might seem low until you remember that Amazon’s top-line revenue includes first-party e-commerce sales). Moreover, releasing AWS’s financials gave investors renewed confidence in the company, giving management freedom to continue investing heavily in capital expenditures for both AWS and the e-commerce business, fueling Amazon’s transformation into a logistics company. The point, rather, is to note that secrets are valuable.

What is interesting to consider is what this means for AI tools like Deep Research. Hedge funds have long known the value of proprietary data, paying for everything from satellite images to traffic observers and everything in between in order to get a market edge. My suspicion is that work like this is going to become even more valuable as security by obscurity disappears; it’s going to be more difficult to harvest alpha from reading endless financial filings when an AI can do that research in a fraction of the time.1

The problem with those hedge fund reports, however, is that they themselves are proprietary; however, they are not a complete secret. After all, the way to monetize that research is through making trades on the open market, which is to say those reports have an impact on prices. Pricing is a signal that is available to everyone, and it’s going to become an increasingly important one.

That, by extension, is why AIs like Deep Research are one of the most powerful arguments yet for prediction markets. Prediction markets had their moment in the sun last fall during the U.S. presidential election, when they were far more optimistic about a Trump victory than polls. However, the potential — in fact, the necessity — of prediction markets is only going to increase with AI. AI’s capability of knowing everything that is public is going to increase the incentive to keep things secret; prediction markets in everything will provide a profit incentive for knowledge to be disseminated, by price if nothing else.

It is also interesting that prediction markets have become associated with crypto, another technology that is poised to come into its own in an AI-dominated world; infinite content generation increases the value of digital scarcity and verification, just as infinite transparency increases the value of secrecy. AI is likely to be the key to tying all of this together: a combination of verifiable information and understandable price movements may the only way to derive any meaning from the slop that is slowly drowning the Internet.

This is the other reality of AI, and why it is inescapable. Just as the Internet’s transparency and freedom to publish has devolved into torrents of information of questionable veracity, requiring ever more heroic efforts to parse, and undeniable opportunities to thrive by building independent brands — like this site — AI will both be the cause of further pollution of the information ecosystem and, simultaneously, the only way out.

Deep Research Impacts

Much of this is in the (not-so-distant) future; for now Deep Research is one of the best bargains in technology. Yes, $200/month is a lot, and yes, Deep Research is limited by the quality of information on the Internet and is highly dependent on the quality of the prompt. I can’t say that I’ve encountered any particular sparks of creativity, at least in arenas that I know well, but at the same time, there is a lot of work that isn’t creative in nature, but necessary all the same. I personally feel much more productive, and, truth be told, I was never going to hire a researcher anyways.

That, though, speaks to the peril in two distinct ways. First, one reason I’ve never hired a researcher is that I see tremendous value in the search for and sifting of information. There is so much you learn on the way to a destination, and I value that learning; will serendipity be an unwelcome casualty to reports on demand? Moreover, what of those who haven’t — to take the above example — been reading Apple earnings reports for 12 years, or thinking and reading about technology for three decades? What will be lost for the next generation of analysts?

And, of course, there is the job question: lots of other entities employ researchers, in all sorts of fields, and those salaries are going to be increasingly hard to justify. I’ve known intellectually that AI would replace wide swathes of knowledge work; it is another thing to feel it viscerally.

At the same time, that is why the value of secrecy is worth calling out. Secrecy is its own form of friction, the purposeful imposition of scarcity on valuable knowledge. It speaks to what will be valuable in an AI-denominated future: yes, the real world and human-denominated industries will rise in economic value, but so will the tools and infrastructure that both drive original research and discoveries, and the mechanisms to price it. The power of AI, at least on our current trajectory, comes from knowing everything; the (perhaps doomed) response of many will be to build walls, toll gates, and marketplaces to protect and harvest the fruits of their human expeditions.

I don’t think Deep Research is good at something like this, at least not yet. For example, I generated a report about what happened in 2015 surrounding Amazon’s disclosure, and the results were pretty poor; this is, however, the worst the tool will ever be. ↩